While the Internet has often been seen as a free, open, indeed liberatory force, certain offline ideologies persist into digital cultures. Further, highly structured technical protocols structure the possibilities for engaging in networked media. Hence, both social and technical forces shape how we express ourselves and how we engage with others in the digital age. These are the codes by which identities are performed online.

Queer Codes compiles eight voices in the emerging, interdisciplinary field of Queer digital visual studies. Together they offer a range of Queer critiques of online media networks, to demonstrate this new field’s broad concerns of how gender and sexualities are depicted and performed online. This collection also represents innovative research developed in the Concordia University art history undergraduate course Queer Networks, a special topic in the histories of New Media Art.[i] Queer Codes collects one possible grouping of the scholarly work created in this course, and owes recognition to the many other exciting, bizarre, sexy, poignant, and truly original ideas raised there.

Class topics developed by our peers range from Queer critiques of robotics and artificial intelligence, online lesbian fan fiction, and alternative music networks, to pinkwashing and corporate control of gay sex services, Grindr selfies, dickpics, and visual case studies from a heritage of radical Queer online presence. Of the many tremendous ideas and possible groupings of essays, this publication highlights one compelling and crucial cluster of research into the history of Queer visual cultures on the Web.

The contributors to Queer Codes pull from an over twenty-year legacy of radical Queer online presence toward a critical discussion of the digital cultures of today. They demonstrate that while digital communications have made Queer representations possible, its technical structures have also constricted the terms by which these representations are configured. Hence, where digital tools have yielded great affordances, the very same tools can be shown to harbour great limitations. And so, where the research collected in this journal demonstrates the range of Queer representation online, it also critiques the ways in which technical systems constrict these performances.

Cason Sharpe, in his reading of the video art of Jennifer Chan, describes how algorithms built into social media networks shape norms of recognisability. Here, hidden structures impose a limited purview of possible performances of the self. Where particular types of gender expression are recognized by these digital systems, artists such as Chan have unsettled the norms by which gender is identified online.

Perhaps these protocols for standardized gender identities are most explicit in pornography networks. Yamina Sekhri develops this critique to expose how the structure of popular porn-sharing Websites caters toward mainstream desires attributed to cis-gender white men. Where this structure excludes sexual and racialized minorities, certain artistic and Queer practices have the potential to intervene and subvert these protocols.

Such structural, systemic biases of online networks can be bent and flexed toward Queerer ends, and Alyse Tunnell demonstrates this in her research of Queer communities on Tumblr. Here, on this popular microblogging platform, Queer-inclusive, safe spaces have been established through critical language use and the sharing of self-determined media. This practice has led to open networks that sustain the validation of trans bodies, Queer erotic desires, and political solidarities.

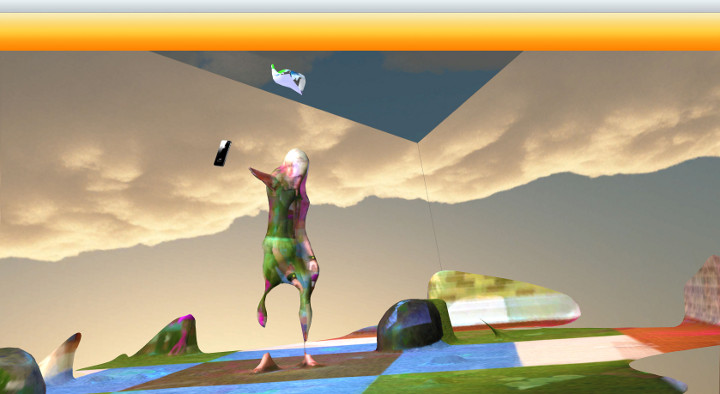

While such critical uses of popular social networks have yielded public voices for Queer communities, others have used the Web to create private spaces. One such space is addressed in the case study of Camille Devaux, which attends to the online subculture of furries. Here, erotic, zoomorphic avatars congregate in media networks designed to foster discourse in gated communities—safe spaces closed to the public, which communally support Queer forms of self-expression and desire.

Through her reading of photos by the artist Emma Gruner, Pauline Soumet situates a heritage of pro-porn Queer feminist critique of mainstream online pornography networks. In appropriating visual tropes of both commercial and amateur porn, Gruner works to disrupt conventions in these hardcore representations of binary gender and sexual stereotypes.

Gruner’s practice owes to a legacy of feminist artists working since the advent of the Web in the mid-nineties. In her essay Stephanie Barclay reads into this legacy to map a tradition extending from early ‘camgirls’ to today’s selfie cultures, in which networked imagery has seen many young women create self-determined digital representations. However, these representations, Barclay’s research shows us, are too-often dismissed as narcissistic and sexually deviant. A contrasting reading of the agential force of these representations instead demonstrates how these girls and women occupy a progressive and provocative online visibility.

Such erotic provocation is central to the videos of Greek artist Georges Jacotey. In her research of Jacotey’s webcam performances, naakita feldman-kiss develops a reading of the artist’s gender-flexible avatar. Here, Jacotey masterfully—if playfully—adopts a stylized mannerism that pulls from pop culture and practices of bedroom Web-camming, to queer a distinction between online and offline selves.

And finally, Louis Angot argues that as the Web further reaches a ‘World-Wide’ presence, its effects are not uniform and equal. For Angot, this is evidenced in amateur viral videos displaying lip-sync pop-song covers by gender and sexually non-conforming youth in Brazil and the Philippines. Unlike much comparable popular online-performance, Angot’s examples demonstrate unique instances of shared social experiences and expressions of non-normative gender online and outside the Imperial West.

Together, these pieces of original research begin to map out key concerns in this new, interdisciplinary study of Queer visual cultures online. They demonstrate that communications networks themselves are not natural nor neutral, but have a role in shaping how digital representations are constructed. Just as offline social structures shape how identities are embodied and performed, these online ‘codes’ come to shape how identity is formed online. Ultimately, through their readings of artwork and visual media objects, we see that Queer codes might push against norms of identity representation in the digital age.

[i] Remnants of this course can be found online: [mikhelproulx.com/queernetworks].

Queer Codes

Studies in Gender, Sexuality, and the Digital

Department of Art History, Concordia University, 2016

Produced by Mikhel Proulx

Co-edited by Sarah Amarica and Estelle Wathieu

This edited collection of papers has emerged from undergraduate student research for Art History 358, Studies in the History of Media Arts: Queer Networks, taught at Concordia University by Mikhel Proulx in the Fall of 2015.

Acknowledgements:

Queer Codes is generously supported by the Department of Art History, the Concordia Council on Student Life, the Concordia University Alumni Association, the Concordia University Research Chair in Sexual Representation and in Documentary, and by the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art. Our gratitude is extended in particular to Cynthia Hammond, Martha Langford, Thomas Waugh, and to the brilliant students of Queer Networks.

All reasonable efforts have been made to contact the creators and rights holders of images printed in this journal. In cases where these efforts have not been successful we welcome communications from copyright holders so that appropriate acknowledgements can be made. We are grateful for image reproduction permissions from Jennifer Chan, Emma Gruner, Faith Holland, Georges Jacotey, Jessica MacCormack, Tom Penney, Molly Soda, Ana Voog, and whatinsomnia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.